Practicing Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

Integrating pest management strategies is important in protecting groundnut yield from pests. While there are many definitions and approaches for IPM, The Southern IPM Center (http://www.sripmc.org/) defines IPM as:

Integrated pest management (IPM) is socially acceptable, environmentally responsible, and economically practical crop protection. Traditionally, a pest is defined as any organism that interferes with the production of the crop. We generally think of pests as insects, diseases, and weeds, but there are many other types, including nematodes, arthropods other than insects, and vertebrates. We now also deal with pests in many non-crop situations, such as human health and comfort.

The Southern IPM Center also suggests the following approach to protecting peanut and other crops from pest injury by using the PAMS approach (Prevention, Avoidance, Monitoring, Suppression):

Adoption of integrated pest management (IPM) systems normally occurs along a continuum from largely reliant on prophylactic control measures and pesticides to multiple-strategy biologically intensive approaches and is not usually an either/ or situation. It is important to note that the practice of IPM is site-specific in nature, with individual tactics determined by the particular crop/pest/environment scenario. Where appropriate, each site should have in place a management strategy for Prevention, Avoidance, Monitoring, and Suppression of pest populations (the PAMS approach). In order to qualify as IPM practitioners, growers should be utilizing tactics in at least three of the four PAMS components. The rationale for requiring only three of the four strategies is that success in prevention strategies will often make either avoidance or suppression strategies unnecessary.

Prevention is the practice of keeping a pest population from infesting a field or site and should be the first line of defense. It includes such tactics as using pest-free seeds and transplants, preventing weeds from reproducing, irrigation scheduling to avoid situations conducive to disease development, cleaning tillage and harvesting equipment between fields or operations, using field sanitation procedures, and eliminating alternate hosts or sites for insect pests and disease organisms.

Avoidance may be practiced when pest populations exist in a field or site but the impact of the pest on the crop can be avoided through some cultural practice. Examples of avoidance tactics include crop rotation such that the crop of choice is not a host for the pest, choosing cultivars with genetic resistance to pests, using trap crops or pheromone traps, choosing cultivars with maturity dates that may allow harvest before pest populations develop, fertilization programs to promote rapid crop development, and simply not planting certain areas of fields where pest populations are likely to cause crop failure. Some tactics for prevention and avoidance strategies may overlap in most systems.

Monitoring and proper identification of pests through surveys or scouting programs, including trapping, weather monitoring and soil testing where appropriate, should be performed as the basis for suppression activities. Records should be kept of pest incidence and distribution for each field or site. Such records form the basis for crop rotation selection, economic thresholds, and suppressive actions.

Suppression of pest populations may become necessary to avoid economic loss if prevention and avoidance tactics are not successful. Suppressive tactics may include cultural practices such as narrow row spacing or optimized in-row plant populations, alternative tillage approaches such as no-till or strip till systems, cover crops or mulches, or using crops with allelopathic potential in the rotation. Physical suppression tactics may include cultivation or mowing for weed control, baited or pheromone traps for certain insects, and temperature management or exclusion devices for insect and disease management. Biological controls, including mating disruption for insects, should be considered as alternatives to conventional pesticides, especially where longterm control of an especially troublesome pest species can be obtained. Where naturally occurring biological controls exist, effort should be made to conserve these valuable tools. Chemical pesticides are important in IPM programs, and some use will remain necessary. However, pesticides should be applied as a last resort in suppression systems using the following sound management approach:

1. The cost benefit should be confirmed prior to use (using economic thresholds where available);

2. Pesticides should be selected based on least negative effects on environment and human health in addition to efficacy and economics;

3. Where economically and technically feasible, precision agriculture or other appropriate new technology should be utilized to limit pesticide use to areas where pests actually exist or are reasonably expected;

4. Sprayers or other application devices should be calibrated prior to use and occasionally during the use season;

5. Chemicals with the same mode of action should not be used continuously on the same field in order to avoid resistance development; and

6. Vegetative buffers should be used to minimize chemical movement to surface water.

Not all of these approaches are available for groundnut farmers in Malawi. As the groundnut industry increases and more resources and technologies become available for pest management, it will be important to integrate tools into production systems. A farmer who follows a control practice may expect a pest or group of pests to be suppressed and yield to be protected, but groundnuts and the environments in which they grow are dynamic and can be unpredictable. When we control one pest, we can affect the ecology of the growing environment and another pest may become a problem. In some cases, the second pest may be more injurious to groundnuts than the first pest. Insecticides can be very effective in controlling insects and protecting yield, but depending on the product used, insecticides can be very disruptive to groundnut ecology.

Scouting Fields

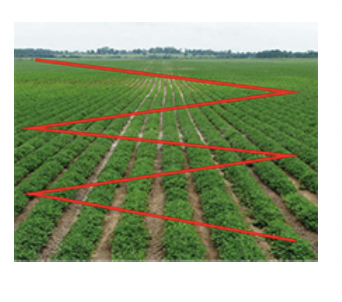

It is important to look for pests in the field and track any change in numbers over time. By documenting the number and type of pests over time, a farmer can see changes that happen within a season or over many years, which can help him choose when and how to apply an intervention. It is important to identify both the pest and the damage the pest causes. A common method of scouting is using a Z-shaped pattern across fields.

Figure 5.5. A typical Z-shaped pattern is used to scout groundnut fields:

Pesticide Use in Groundnuts

Pesticides can be effective tools for pest control but can be harmful to human health and the environment when used inappropriately. Individuals applying these products need to wear protective clothing, gloves, boots, goggles and a respirator depending on the product they are applying. The correct rate should be applied to prevent leaching into groundwater or movement from fields into sensitive areas and ensure pest control and prevent unnecessary injury to groundnut.

Pesticides should be placed in a cool and dry space away from stored seed and harvested crops. It is especially important to store pesticides in a way that people, especially children, are not exposed to them. Keep the pesticide tightly sealed in the original container and do not store pesticides in containers that could be confused with those used for cooking, drinking and food storage. Every year many people around the world are poisoned by pesticides, most often due to accidental exposure in storage areas or in households. Using pesticides that are sanctioned by the Malawi government and used in the appropriate way will also ensure that residues of pesticides do not contaminate foods consumed by people.

When pests are present and active, pesticides can be very effective in protecting groundnuts and minimizing yield loss. They can suppress pest populations quickly and reduce the labor needed for pest management, especially in the case of weeds. However, pesticides do pose a risk to people, the environment and the food system if they are used improperly. Pesticides should be respected and used in manner that protects people and the environment.

Impact of Arthropods on Groundnut Yield

Groundnuts can be affected by multiple pests including termites, aphids, Hilda spp., white grubs and leafminers. Crop rotation typically helps to prevent or reduce all insect pests. Early planting, higher plant densities, and practices that ensure a healthy plant (proper soil pH and fertility) reduce the impact of pest problems. Before implementing any specific control practices, a farmer must scout the field, measure the level of infestation and find where the pest is in the field to determine if action is warranted. Some pests such as groundnut rosette can be partially managed through the selection of resistant varieties.

Termites: Termite can damage groundnuts at all stages of growth but are usually most serious close to harvest when the soil is dry. These pests occur anywhere groundnuts are grown in Malawi, but infestations usually are in patches. Termite damage can reduce yield and quality and makes the kernel more susceptible to mold and aflatoxin contamination. Termite infestations can be reduced by deep ploughing and incorporating crop residues into the soil and using chlorpyrifos on infested areas.

Groundnut aphids: Aphids are vectors of groundnut rosette disease and can significantly hurt yield, especially during drought. They suck sap and plant juices from the plant's growing points. Aphid damage and the transmission of groundnut rosette can be minimized by planting early, destroying volunteer groundnut plants, and using resistant groundnut varieties (e.g., Baka).

Hilda species: This pest is associated with black ants, and is found most often in early- or late-planted fields. Damage usually begins along the field edge and is most serious in drought years. Areas if infestation are often seen in patches of wilted and dead plants.

White grubs: Insect larvae (grubs) feed on roots and pods, causing wilting and exacerbating drought stress. They are most common in the light sandy soils of the Lilongwe plateau. Crop rotations help reduce all insects.

Leafminers: This insect tunnels or "mines” through the leaf tissues and produces blister-like lesions on the leaves. Severe infestations can cause the leaflet to become brown, shriveled and will dry up. Whole plants can die from severe infestation. Leafminers are not able to move long distances and local infestations can usually be controlled. They are most common in northern Malawi.

Insecticides Guidelines for Groundnuts in Malawi

There are many trade names for pesticides. In this listing, they are referred to by the common name for the active ingredient and a few examples of trade names listed in parenthesis. When purchasing any insecticide, look beyond the common name to make sure the product contains the active ingredient you are seeking. Read and follow all label directions and make sure the product is registered for use on groundnuts. There are three main groups of insecticides: organophosphate, pyrethroid, and neonicotinoid insecticides.

Organophosphate Insecticides

Insecticides in this group are highly toxic to humans and animals as compared to the other products. The common names often end in “fos” or “phos”. These products are typically very broad spectrum (i.e., control a number of insect species) and are very effective. These products usually have relatively long residual activity (except acephate) and many are effective against soil insects. Typically, they work well on ants, aphids, caterpillars, jassids, leafminers, and some work on termites, white grubs, and nematodes.

Pyrethroid Insecticides

These insecticides are typically used at lower doses and are very effective against caterpillars and aphids. Products that are pyrethroids all have common names that end in “thrin”. They are less toxic to people and animals than organophosphates are. They have shorter residual activity and are generally not effective against insect pests in the soil.

Neonicotinoid Insecticides

These insecticides are among the safest products and have a relatively broad spectrum of control, good residual activity, and good protection against many soil insects.

Seed treatments

Treatment of seed prior to planting can provide value for groundnut production programs in Malawi. These may contain only a fungicide such as Thiram to protect the seed and seedling against various soil-borne diseases. Some seed treatments also contain an insecticide usually imidacloprid or thiamethoxam. These can help protect the seed and seedling against a variety of pests such as white grubs, millipedes, ants, wireworms and as the plant emerges offer some control of aphids and jassids. Common trade names include Cruiser 350 FS (insecticide only), Apron Star (thiamethoxam, metaxyl, and difencomazole), and Gaucho T (imidacloprid, Thiram).

As with all pesticides, users must wear appropriate protection and follow proper handling recommendations. Any seed treatment should be applied to the seed just prior to planting, and any seed that is not planted should be destroyed so that no one eats it.

Impact of Diseases and Viruses on Groundnut Yield

Leaf spot diseases, rust and crown rot are fungal diseases that affect groundnut yield in Malawi. Rosette, which is caused by viruses spread by aphids, also can be a problem.

Figure 5.6. Early leaf spot (ELS) causes brown spots with a yellow halo.

Figure 5.7. Late leaf spots (LLS) forms dark brown or black spots with a less brilliant halo.

Figure 5.8. Rust forms reddish-brown pustules on the underside of the leaf.

Figure 5.9. Crown rot causes the main stem of seedlings to rot, killing the plant.

Figure 5.10. In chlorotic rosette, young leaves turn yellow.

Figure 5.11. In green rosette, plants are severely stunted.